IMJS: Japanese Cultural Heritage Initiatives

Columbia University

Treasuring the Past・Enriching the Present・Transforming the Future

Celebrating 20 years of Japanese Heritage Music program

View the ProgramPast Events

Video Library

Visiting Scholars

About

The overall purpose of the Institute is to encourage research on neglected aspects of premodern Japanese civilization, especially during the medieval period (primarily, but not exclusively, the Kamakura and Muromachi periods 1185-1600), centuries which, until the 1970s, had received scarce attention by Japanese and Western scholars alike.

• History

• Past Activities

• IMJS Reports

• Organization Staff

• Contact Us

• Collaborators

• News

- Home

- EMAJIN Project: Gagaku-Hōgaku at Columbia

- IBC Project Textile Conservation

- IBC Project Research & Restoration

- About Us

- Support

- The Songs of Otomae

- Video Library

- Gagaku Dayori

- 50th Anniversary Celebration: 1968 – 2018

- 50th Anniversary Celebration: 1968 – 2018

- Thank you for your registration!

- Thank you for your message!

- tokyo50

407 Kent Hall

1140 Amsterdam Avenue

Columbia University

New York, NY 10027

USA

In conjunction with the Gagaku-Hōgaku Classical Japanese Music Curriculum and Performance Program at Columbia University, launched in September 2006, the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies presents several public gagaku concerts and instrumental workshops to introduce the ancient music of Japan to a greater audience at Columbia University and in New York.

In conjunction with the Gagaku-Hōgaku Classical Japanese Music Curriculum and Performance Program at Columbia University, launched in September 2006, the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies presents several public gagaku concerts and instrumental workshops to introduce the ancient music of Japan to a greater audience at Columbia University and in New York.

Concerts

Leading gagaku artists are invited from Japan to perform at our New York concerts. Members of the renowned gagaku ensemble Reigakusha, such Mayumi Miyata (shō), Hitomi Nakamura (hichiriki), and Takeshi Sasamoto (ryūteki), have presented pieces from the classical repertory as well as contemporary compositions for the ancient gagaku instruments. The concerts are an important showcase for newly-commissioned works for gagaku instruments. At the March 2006 and February 2007 concerts, new compositions by Hiroya Miura, commissioned by the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies, were given their world premieres. These musical gatherings are also an opportunity for collaboration between musicians and artists from Japan and the United States, as well as between performers of eastern and western instruments. In November 2006, the gagaku musicians and bugaku dancers of the Ono Gagaku Society of Tokyo performed with Shrine Celebrant Kagura Dancers from the International Shinto Foundation in New York.

Workshops

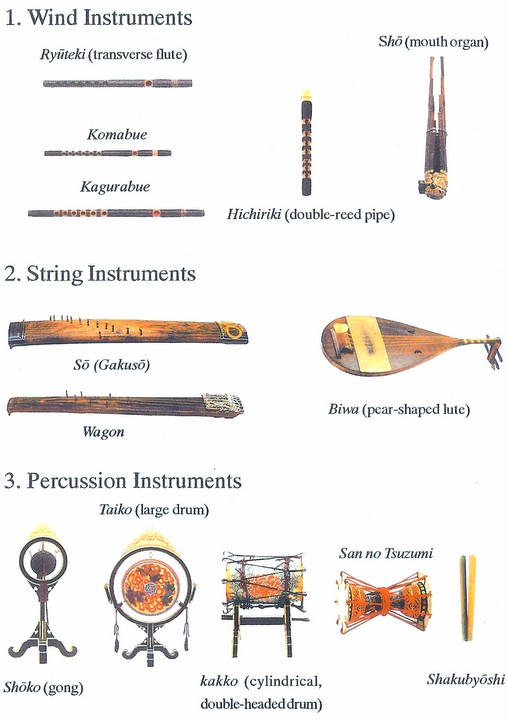

Visiting gagaku artists from Japan also lend their expertise by providing instruction for open instrumental workshops. Participants, including both beginners as well as professional musicians, gain hands-on experience with their choice of the three gagaku wind instruments: hichiriki, ryūteki, and shō.

Japanese court music (gagaku) is the oldest continuous orchestral music in the world today, with a history in Japan of more than 1300 years. The term gagaku itself, which means elegant or ethereal music, refers to a body of music that includes both dance (bugaku) and orchestral music (kangengaku) handed down over the centuries by professional court musicians and preserved today by musicians belonging to the Imperial Household Agency in Tokyo.

Gagaku can be divided into three categories according to origin: 1) indigenous vocal and dance genres, accompanied by instruments and employed in imperial and Shinto ceremonies; 2) instrumental music and dance imported from the Asian continent during the 5th to the 9thcenturies; and 3) vocalized poetry in Chinese or Japanese set to music from the 9th to the 12thcenturies. The best known and most frequently performed is the music of the second category, known as Tōgaku (if of Chinese and continental origin), or Komagaku (if of Korean origin). Classical Tōgaku pieces are performed by large instrumental ensembles of up to thirty musicians, consisting of shō (mouth organ), hichiriki (double-reed pipe), ryūteki (transverse flute), biwa (pear-shaped lute), koto (long zither), taiko (large drum), kakko (cylindrical, double-headed drum), and shōko (bronze chime). When accompanying bugaku dance, however, the Tōgaku ensemble consists only of winds and percussions.

Gagaku is comprised of many musical traditions and influences that traveled the Silk Road from the Middle East through Central Asia and Tibet, flourished in T’ang Dynasty China (618-907), and finally journeyed further to Korea and Japan. Although this musical heritage has been abandoned in many other countries, this ancient orchestral music continues to be performed and preserved in Japan, a country where foreign cultural imports were readily absorbed and where aspects of ancient high culture were revered and rarely abandoned. Without a doubt, gagaku, in tempo and even in certain melodies, is not today what it was in ancient Japan or on the continent, but in many ways, today’s gagaku may be the only living evidence of those ancient musical ensembles, their musical instruments, musical sounds, and the musical cosmology of the Asian continent and of ancient Japan.

Until at least the 1960’s, due in great part to the Imperial Household Agency’s mission to preserve permanently musical forms that are more than a millennium old, gagaku musical traditions were transmitted as faithfully as possible to their originals. Over the past few decades, however, some imperially-trained musicians have become increasingly aware that preservation alone is not enough to keep an art alive. Pioneers such as former Imperial Household Music Department member Sukeyasu Shiba, who created the Reigakusha gagaku ensemble outside of the court, have held an important role in training new artists. His and other similar ensembles are impacting the present-day international musical scene with their performances of gagaku compositions, both classic and contemporary.