Origins of the Institute

The modern libraries of Japan and the West today tell us something of the way twentieth-century scholarship, both in Japan and abroad, has distorted the shape of Japan’s pre-modern cultural history. In almost all disciplines in the humanities, studies of the four hundred years prior to 1150 and the more than four hundred years from 1600 to our present day dominate the bookshelves. But that longest period of recorded Japanese history, that traumatic cycle of medieval time stretching more than five hundred years from the Genpei cataclysm to the seventeenth century, remains so unevenly researched that our perspectives on the day-to-day existence of medieval Japanese men and women remain embarrassingly inadequate when not in outright error. A seemingly unbridgeable gulf has lain between twentieth-century research on medieval Japan and what we all, in every discipline, need to know about medieval Japanese life in order to give context, and thus meaning, to the facts we already know. Despite the high level of achievement reached in recent years in the historiography of medieval institutional and political life, the ordinary texture of the medieval Japanese social and cultural experience remains still highly elusive. Even the great high culture of the medieval years, which has always attracted the serious attention of humanists, remains narrowly focused, and therefore inadequately explicated and theoretically immature.

The social, intellectual, and cultural history of medieval Europe represents one of the most sophisticated of interdisciplinary achievements in the Western academic world. By contrast, knowledge of medieval culture in the Japanese context is primitive indeed. There have been excellent studies of the military, political, and economic constituents of Japanese feudalism. Histories of medieval institutions have been written. Biographies of leading political, religious and literary men and studies of elite intellectual and artistic pursuits have been published. And yet we still have not begun to approach, in humanistic terms, a definition of medieval Japanese cultural history nor to understand what the medieval experience meant to the vast majority of the men and women who lived it. The almost total absence of women from our discourses on medieval Japanese religious, literary, and art histories is symptomatic of this endemic neglect.

In short, medieval humanistic studies represents perhaps the most sorely neglected area of Japanese Studies today. It is to the rectification of this situation that the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies was originally founded.

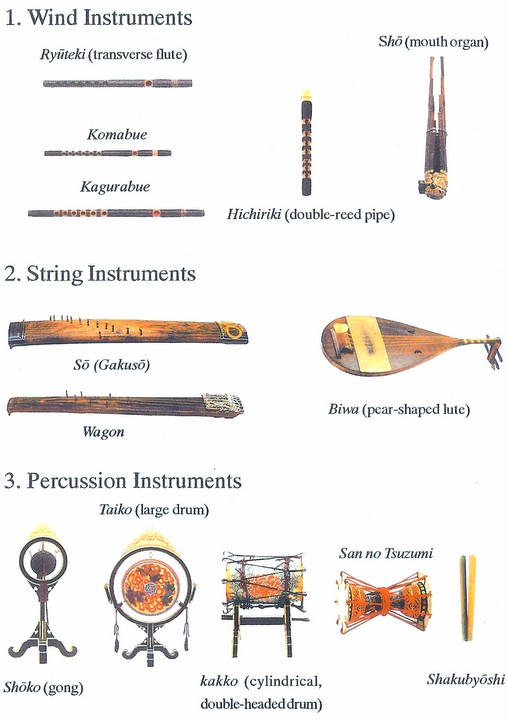

In conjunction with the Gagaku-Hōgaku Classical Japanese Music Curriculum and Performance Program at Columbia University, launched in September 2006, the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies presents several public gagaku concerts and instrumental workshops to introduce the ancient music of Japan to a greater audience at Columbia University and in New York.

In conjunction with the Gagaku-Hōgaku Classical Japanese Music Curriculum and Performance Program at Columbia University, launched in September 2006, the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies presents several public gagaku concerts and instrumental workshops to introduce the ancient music of Japan to a greater audience at Columbia University and in New York.