Summer Seminar

Kenkyukai: Nihon no josei to bukkyo Summer Seminar 1993

The Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies is in receipt of Japanese language abstracts and handouts from the 1993 Summer Seminar of the Kenkyukai: Nihon no josei to bukkyo held at the headquarters of the Rissho kosei kai in Tokyo, August 25-27 with more than 60 in attendance.

Katsuyo MOTOYOSHI has prepared brief English summaries of these abstracts and we are pleased to publish them here for the convenience of all our readers, especially those studying Women and Religion outside the Japan field.

In addition to the four papers presented at the Summer Seminar, Dr. Paula ARAI gave a special report on her recently completed (May 1993) Harvard University doctoral dissertation “Soto Zen Nuns: Living Treasures of Japanese Buddhism.” This study “examines the lives and self-perceptions of Zen monastic women” and is the result of “an extended period of participant-observation in a Zen monastery for women, extensive interviews, and responses to [a] national survey of female monastics.” In addition to chapters on current monastic practices of Zen nuns, the dissertation includes a survey of women monastics throughout Japanese history and an analysis of the 20th century revival of the female monastic tradition.

Those who wish to read Dr. Arai’s dissertation may write to her at her current Hong Kong address (listed on page 5). We give as well the addresses of the four Japanese scholars whose papers are abstracted herein so that those interested in opening correspondence and pursuing their topics in more detail may do so directly.

English Translations of Abstracts

On “Datsueba”

by KAWAMURA Kunimitsu

“Datsueba” is an old lady demon who is one of the keepers of Hell and whose function is to strip the clothing from the sinners when they first arrive at the riverbank of Hell (sanzu no kawa). She makes her first appearance in Japan in the Bussetsu Jizo bosatsu hosshin innen juo kyo, a late spurious Chinese sutra dealing with the Bodhisattva Jizo and the Ten Kings of Hell. Datsueba is paired with an old man demon. Datsueba breaks the fingers of the sinner as a punishment for stealing, and together with the old man, she ties the sinner’s head to his feet. Then the old woman strips the sinner, and the old man hangs up the garments on a tree branch. After this, the pair send the sinner off to the judgment court appropriate to his sin.

The next work that refers to Datsueba is Hokke genki of 1043. Another source from 1257 also mentions that when the sinner has no clothes to strip, she strips his skin. She also appears in a Muromachi monogatari called Tengu no dairi.

It could be argued that Datsueba is not merely a demon who strips the garments of a sinner, but she is also a kind of goddess who presides over the dead. Not only does she strip the dead, but at the time of birth it is also she who bestows on humans their coverings (skin). Thus she can be seen as a goddess of both life and death who both gives and takes away the skin that covers humans.

Japanese “pollution” (kegare) and the system of excluding women from sacred sites (nyonin kinsei)

by MIHASHI Tadashi

The feeling of uncleanliness and dislike evoked by the word “pollution” is probably based on universal human emotion, but the objects associated with this notion seem to vary from time to time and culture to culture. While Buddhism on the one hand considers the physical world itself and thus mankind, too, as “polluted,” the ancient Japanese mytho-historical texts like the Kojiki and Nihon shoki, too, contain a concept of pollution that has generally been interpreted as equated to “sin.”

One distinction, however, must be made between the interpretation of pollution in Engishiki and that of the two texts mentioned above. The Engishiki has as its basis pollution laws influenced by Tang Chinese texts, and it would be a mistake to see its concept of pollution as simply based on a continuity from the ancient Japanese world of the Kojiki. Engishiki treats pollution as something contagious caused by death, birth and loss of fire, and while this may be influenced by the death of Izanagi when she gives birth to the fire god, the general treatment of pollution in Engishiki is by contrast quite materialistic.

Up until the mid-Heian period, the notion of pollution which was widespread among court society was largely associated with the political structure centered on religio-ritualistic functions upon which pollution was regarded as dangerous and a negative influence. Later the concept spreads further into the realm of personal worth, and with the transformation of the political role of the ritual religion, the object of pollution became more and more generalized. And by the late-Heian period, the orientation shifts from state sponsored rites and festivals to regulations concerned more with personal pilgrimages and to particular religious institutions. This shift from the state to particular institutions can also be seen in the Kamakura period pilgrimage guidelines established for various religious centers.

The expansion of the concern to ward off pollution during the middle ages has often been explained in terms of the expansion of governmental influence or the influence of the class system, but such explanations seem unnecessary in view of the fact that such fear of pollution was never anything more than a deep-rooted religious fear of pollution shared by many.

The assumptions which link the medieval development of restrictions against women with the spread of pollution laws must be reevaluated. Within the context of the medieval development of pollution as a concept, the idea of “woman as pollutant” never appears. The reason why women were not allowed to enter sacred mountains seems to have been more a practical consideration in view of the fact that these were designated sacred training grounds for dedicated men of religion. The idea of woman as pollutant may have appeared merely as a later rationalization to aid ascetic men.

A reevaluation of the relationship between Shinto & Buddhism: transformation of the idea of “impurity” and the nature of “jissha-shin” or “true” Shinto deities

by NAKAMURA Ikuo

In the Middle Ages, the rise of Nenbutsu Buddhism, where even the lowest sinner could be saved by calling on the name of Amida, helped dismantle and restructure the ancient notion of ritual impurity, and this has in turn affected the development of medieval Shinto worship.

In his work Honen rejected the notion of ritual impurity as an impediment to one’s salvation as long as one relied exclusively on intoning the nenbutsu. By doing so, he tried to establish a new religious path to salvation for all, which had been denied by both the Shintoistic world view and Buddhist orthodoxy.

From the criticism directed at Honen and their followers, it is clear that the issue of sex and meat-eating were the two greatest point of controversy between the practitioners of Nenbutsu Buddhism and the Buddhist orthodoxy. The orthodox held that a monk must avoid these two sins at all cost, whereas Honen and his followers allowed them.

The conflict between the old and new Buddhisms not only involved the interpretation of traditional notions of sin and impurity, but it also initiated the fundamental restructuring of ancient religious paradigms. The division of Shinto deities into jissha-shin and gonsha-shin was first expressed by the monk Teikei of Kofukuji Temple in the context of his attack against Nenbutsu Buddhism. Teikei divided Shinto deities into jissha-shin or the “true type” who are manifestations of demons and spirits, and gonsha-shin who, according to the theory of Honji-suijaku were originally Buddhas and Bodhisattvas and have manifested themselves in the forms of Shinto deities. Teikei attacked Nenbutsu Buddhism’s disrespect towards the gonsha-shin deities as somehow “lesser.” This trend toward valuing jissha-shin deities over gonsha-shin deities can be found in other writings, but on the other hand, the true or essential type deities were considered as lower beings in such vocally narrated honji dan as the Shinto-shu. Yet in such works these lesser deities acquire a new sacred status as “suffering gods” who have fallen into impurity and a demonic state. Such phenomenon could be interpreted in the context of the transformation of religious outlook brought about by the rise of the new Buddhism and its conflict with its orthodox predecessors.

Priestesses and girl children: a re-evaluation of the role of the “mono-imi” of the Ise Shrine in ancient times

by YOSHIE Akiko

From ancient times until the Meiji period, a prepubescent girl filled an important ritual post known as mono-imi at the Ise shrine. Traditionally this role has been interpreted as another example of female prominence in Japanese ritual. The present study endeavors to challenge this assumption and to reevaluate the facile association between women and ritual by scrutinizing the ritual roles played by male and female adult couples that have been obscured behind the prominent attention hitherto given to the role of prepubescent girls and virgins.

Making ritual offerings is one of the most important functions of the mono-imi, but sources such as “The Ritual Record” (Gishikicho) of 804 indicate that the offerings of fish and seafood were made by male priests while those consisting of grains and liquor were made by mono-imi. This role division points towards the original ritualistic division of labor between men as hunters and fishermen and women as agricultural workers. It would therefore seem that the original ritual role of shrine priestesses was filled by adult women as a partner in the communal economy rather than by prepubescent girls. Recent studies have indicated that woman’s ritualistic involvement was based more on her role as an equal partner in a pair made up of fertile and productive males and females. In this context too, the ritualistic prominence of prepubescent girls or virgins seems to be a later development.

The use of prepubescent girls as mono-imi could not have been based on ritual restrictions against adult women’s menstrual fluid. The oldest record of mono-imi being released from her role for this reason is from the 13th century. In ancient times, there was no ritualistic restriction against women because of menstruation.

New Discoveries

Heretofore unknown letters and koan-poems written by and in the hand of the 13th century Zen Abbess, Mugai Nyodai, were discovered in October by Professor Barbara Ruch at Daishoshi convent in Kyoto in the course of a new Buddhist convent survey project that she has initiated through the National Institute of Japanese Literature and which is funded jointly by the Japanese Ministry of Education and the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies. A heretofore unknown Edo period Nara ehon illustrated manuscript book purporting to tell the story of Mugai’s enlightenment was also found at Hokyoji convent. The survey project will continue over the next several years.

New Book Information

Look for Kathryn A. Tsai’s new book, Lives of the Nuns, from the University of Hawaii Press this summer.

NOTE

We are in receipt of Professor KATSUURA Noriko’s offprint of her 1993 chapter (in Japanese) on the differences in the usage of secular vs. religious names and ranks for Buddhist monks and nuns as revealed in the eighth century Shoku Nihongi and twelfth century Taiki. We will send a xerox copy to anyone interested.

[ Volume 5 of IMJS Reports was compiled by Angela E. Okajima ]

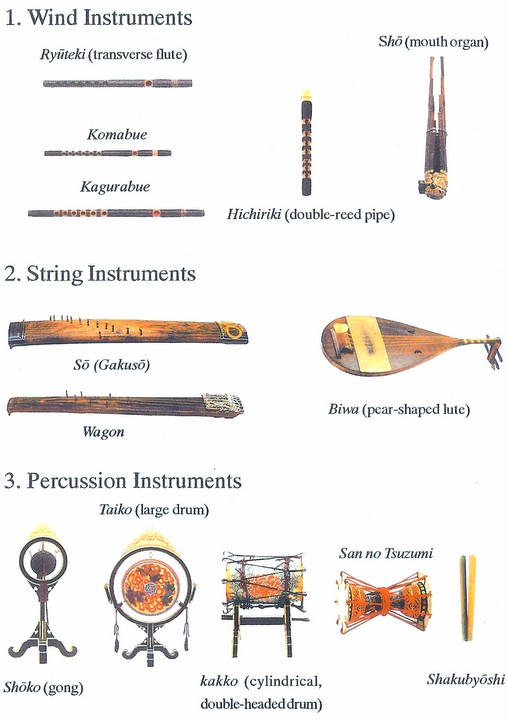

In conjunction with the Gagaku-Hōgaku Classical Japanese Music Curriculum and Performance Program at Columbia University, launched in September 2006, the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies presents several public gagaku concerts and instrumental workshops to introduce the ancient music of Japan to a greater audience at Columbia University and in New York.

In conjunction with the Gagaku-Hōgaku Classical Japanese Music Curriculum and Performance Program at Columbia University, launched in September 2006, the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies presents several public gagaku concerts and instrumental workshops to introduce the ancient music of Japan to a greater audience at Columbia University and in New York.